I will pick up a thread from my earlier post on Charles Mills: he writes at one point in The Racial Contract about racism as a “a problem of cognition and of white moral cognitive dysfunction,” and while I hinted around the challenges that idea might pose for intellectual historians, I want to think about that more directly.

Intellectual historians often hold themselves to a particular standard when it comes to representing the mental worlds of individuals who have left behind enough evidence for us to make conjecture about thoughts they might have had but which they never made explicit, or which they expressed in contradictory ways. That standard is something like: write about this person in such a way that they would recognize themselves in your writing.

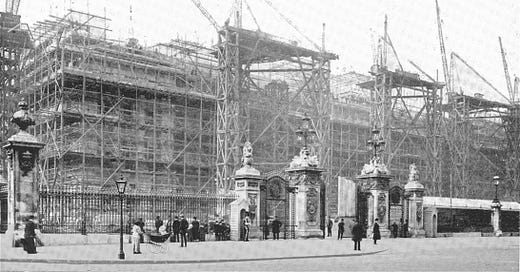

That doesn’t mean that you must try to present them as they would describe themselves, or that you can’t show them “warts and all,” even if they would prefer you to airbrush those blemishes out of your account. But it does mean that you cannot really call them deceitful if they believed they were truly honest, or cruel if they believed that their worldview was thoroughly fair. You have to do the work of surmounting whatever repugnance you might have for them and try to reconstruct the mental gymnastics they performed to maintain a self-image of honesty or fairness or whatever. Or maybe a better metaphor is: you have to rebuild the mental scaffolding they pulled up around themselves such that they could continue to build their self-image higher and higher without having to start over and knock everything down to the foundations.

You cannot, then, just knock that scaffolding away and declare, “behold!” That would be a violation of the rule that your portrait of them must be one they would recognize: while they might not think very often about the scaffolding that drapes their exteriors, they would feel naked if you left it out.

Mental scaffolds that intellectual historians ostensibly should leave in their portraits might include specific dogmas (although we aren’t generally permitted to call them dogmas) and contemporary social mores. If slavery is prevalent in that society, that probably plays a role in how an enslaver thinks about their own character and morality; we are not supposed to speculate too much about how the experience of being an enslaver might have warped that person’s ability to observe and process the world around them, e.g., that enslaved people display intelligence, manifest a typical range of recognizable emotions, feel pain.

But why not? What do we owe to the past such that we cannot say, effectively, racism is—whenever it appears—a cognitive impairment? Why must we characterize such a statement as “imposing our values” when it is actually an empirical proposition, namely that a single person will respond to two otherwise identical set of sensory and social cues in radically different ways if the single factor distinguishing those two situations is the races of the people involved.

Perhaps historians don’t like talking about “impairment”—it seems too judgy, implies a kind of stigma. But not all impairments are stigmatized, and even those that are may once have not been considered shameful or may even have been ignored entirely. What if we were to think about racism as a cognitive impairment that has acquired (in the eyes of many but not all) a stigma but that used to be mostly unstigmatized?

Intellectual historians, I think, are drawn to the puzzle-like nature of trying to reverse-engineer the mental scaffolds of their subject. It is not just those subjects that may be exposed if the scaffolds are suddenly stripped away—intellectual historians might feel they have nothing to do, except point—well, there it is—and, maybe, blush.

You make a comparable argument about patriarchy and cognitive impairment here: https://s-usih.org/2014/02/the-problem-that-has-no-name-guest-post-by-andrew-seal/ Which reminded me of this article: https://www.christiancentury.org/article/2012-01/uncredited